Multi-Lingual Online Dialogues?

7. January 2009 – 11:04 by Hans HagedornOne of the main challenges developing an international or pan-European online-dialogue lies in translating the user-generated comments. While the translation of editorial texts and navigation elements is a one-time-effort, the translation of user generated content (UGC) is a continuing, therefore expensive and time-consuming process. Language used in UGC resembles more natural, spoken language, which makes it difficult to translate automatically. Furthermore, you can not know for sure how much content the users will produce.

Using international or transeuropean online-platforms might remind you of the Tower of Babel: A lot of languages, but no mutual understanding, no mutual debate. Photo by mharrsch, flickr.com, CC by-nc-sa 2.0

A lot of pan-European projects try to evade this problem and offer their content either in English only or in some other “big” European languages like French, German, and Spanish. Online-Forums as “Debate Europe”, which we introduced a few weeks ago, are even available in all 27 national languages of the European Member States – but the users comment just in their own language, only a few texts are transferred into all languages by professional EU-translator. Participants capable of speaking and writing English use the English-language forum to discuss topics with members from other nations.

But while a lot of Europeans can speak and understand English that’s by far not true for all. Especially elderly people and people with a lower level of school education are left out of the debate. And even for many educated professionals, writing in a foreign language is more demanding than using their mother tounge. This is one of the main obstacles preventing a pan-European public sphere.

So, how can you involve a broad sample of citizens regardless their language capabilities and enable an equal dialogue between participants from different nations? Here we want to give some examples of strategies already in use. It’s meant as an introduction to different possibilities; none of them might be the ultimate answer and not every method might work in all environments.

Professional Volunteers

Working with professional translators on a volunteer basis is one approach to save money while still assuring a qualified output. Global Voices, a non-profit foundation situated in the Netherlands, chooses this approach. The project, first set up by the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University, wants to make voices heard that usually go unnoticed by mass media, especially in the developing world. Therefore, the websites aggregates the global discussion in the Internet, with volunteer bloggers and editors working as a guide to the international blogosphere. Global Voices Lingua, a side-project, seeks to develop and broaden a network of volunteer translators. They transfer the blogposts from all over the world into recently 15 languages (e.g. Chinese, German, Farsi, Hindi, Serbian and others). In this way the blogposts are made accessible for a greater, international audience.

A similar approach, relying largely on volunteer staff, is used by Café Babel. The pan-European and multi-lingual online-magazine wants to offer a platform for participative journalism and to generate a transeuropean public. Café Babel offers editorial articles in seven languages: English, French, German, Polish, Italian, Spanish, and Catalan. Journalists in local editorial offices situated all over Europe write and edit articles in their own language. Volunteer translators transfer the texts into every other of the seven languages.

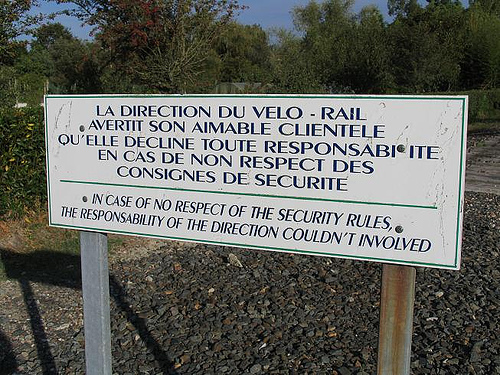

Users have different possibilities to participate: First off all, they can comment on the articles – here they can choose in which language they want to contribute. Second, Café Babel provides online-forums on a variety of topics, ranging from political questions to sports and culture. While the topics are the same for all seven offered languages and the initial comments are translated into some of the languages, the following user comments are not. Café Babel povides stats, showing which discussion is available in which language and how many comments are posted there. As a third possibility, registered users can write their own weblog. Here, each author can choose in which and in how many languages he/she wants to offer his/her content.

Screenshot of Café Babel Forums: In the section below the actual forum you see the stats for the different languages.

Multi-Lingual Press Review

A more professional approach shows euro/topics.net, a multi-lingual press review by the German Federal Agency for Civic Education. Euro/topics.net differs from the projects mentioned above insofar as it does not provide any user generated content at all. Instead, the website consists of a daily press review of European newspapers, also available as a newsletter. Additionally, every week a dossier on a specific European topic is published. For euro/topics.net, the Federal Agency for Civic Education works together with n-ost, the “Network for Reporting on Eastern Europe”. The editors and correspondents, professional journalists and translators, choose the most important articles from the 27 member states and translate a short abstract into the four languages presented on the website, English, German, French, and Spanish. The weekly dossier is translated, too.

User Generated Translations

A different approach concentrates on using the strength of UGC and the community building effects of web 2.0 themselves: a collaborative, user generated translation. The probably best known effort of this kind was undertaken by Facebook: When translating the Social Network into Spanish and German, it was up to the users to transfer the texts from English and to come up with suggestions for typical Facebook-expressions like “poke” (which e.g. now translates into German as “anklopfen” – to knock). Translations for difficult expressions were revisited and voted on by the users.

This method allows saving a lot of money for translation efforts, while the outcome seems to be quite satisfying. Also, it strengthens the community; the users feel to be taken seriously. But it still is rather time-consuming – and you have to note that merely the static parts of Facebook were translated, not the UGC itself. Furthermore, this approach might work best for already established online-platforms with a critical mass of users from different countries.

Machine Translation

Most projects we reviewed use Human Translation; Machine Translation (MT), especially the rule-based method (see Wikipedia), works best with highly structured text, but has flaws when it comes down to more natural language with aberrations from common grammar and a variety of out of vocabulary words - like it is the case with UGC.

Sometimes Machine Translation comes up with rather odd suggestions. Photo by eco-photography, flickr.com, CC-by-nc-nd 2.0

Recent tools and programmes like Google Translate or Language Weaver, to mention just the two possibly best known, use a different method: the so-called Statistic Based Machine Translation, SBMT (see Wikipedia). In an nutshell: For SBMT, a huge corpus of bilingual texts, most common parliamentary protocols, sometimes books published different languages, are fed into a computer. On a statistical basis, the computer gets able to discern patterns and to translate texts even when certain rules of grammar do not apply or are not yet defined.

Translation quality still is considerably poorer than using Human Translation; but even if the grammar is sometimes a bit mixed up and seems a bit odd, the texts can still be understood easily.

Combined Approach?

Our next thought was to look for a mixture between SBMT and human revision, which combines the advantages of both: High volume, low cost, high quality, community approved translation (also called “HVLCHQCAT” :-)). However we could not identify any project of this kind. So we are considering building it ourselves… Any hints or comments are welcome!

Simone Gerdesmeier, Hans Hagedorn, Zebralog

5 Responses to “Multi-Lingual Online Dialogues?”

By Simon Smith on Jan 9, 2009

Many thanks for such a useful summary of the field!

Many non-English speakers I meet across Europe strike me as strangely ambivalent about the current dominance of English (or perhaps I should say the ‘big’ European languages as a group?) in online discussion about Europe. I think it is a problem, and that it is becoming a ‘divide’ every bit as disenfranchising as the digital one where European democracy is concerned. Ironically the digital divide contributes to this linguistic disenfranchisement by creating the technical means for a European public sphere, but making the vast majority of it accessible only to those who are fluent in English (or possibly French, German, Spanish).

So thanks for publicising some interesting attempts to combat this trend.

Having said that, there is a possible counter-argument here that intrigues me. Debating in national ‘enclaves’ about Europe may have some advantages over a pan-European online discussion even if we could ’solve’ the language problem. For example, it may involve more or a broader cross-section of people, since European affairs are more eye-catching when they have a national, regional or local dimension (as the European Commission recognised in its attempt to ‘go local’ with the Plan D events). In Britain, certainly, European issues have very little popular appeal until they are explained in terms of how they affect life in Britain (or at a much more local level than that). Debates about Europe without this local angle attract only a few ’specialists’ like myself.

Secondly, if you’re looking for agenda-setting ideas and proposals from an eParticipation process, then you may - possibly - get a broader range by consulting national ‘communities’ separately instead of organising a pan-European ‘brainstorming’ process (although I would love to compare the two!)

For those reasons I quite like the design of the European Citizens’ Consultation (covered here in a recent blog post), which has national online discussion followed by face-to-face pan-European discussion (involving, of course, only a small randomly selected sample of citizens). It may prove to be quite a fortuitous design choice even if it was made due to purely technical or resource considerations. But what would add greatly to the process is to integrate some kind of secondary translation system as practised by Global Voices, so that interesting user-generated content from the ECC national forums could be gradually made available in all EU languages across the forums, perhaps feeding into a second round of online discussion. If the organisers are reading this, it would be interesting to know if they have any such plans.

By Zebralog on Jan 17, 2009

Hi Simon, I agree, that a tiered approach for large-scale online-dialogues can be a good thing to cope with the amount of issues and opinons. However, I do not see the benefit of national sub-discourses when the topic at hand is a European or global one.

Rather I believe, that the “Joe the Plumber” and “Hans der Klempner” have much in common. At least more than a plumber and an investment banker in one country. Yes, European issues should be viewed in smaller dimensions, which affect the single citizen. However, if those dimensions are always defined by national boundaries, we will never get rid of national egoisms. And thus will never be able to solve some of the larger international challenges.

Best wishes, Hans Hagedorn

By Simon Smith on Jan 20, 2009

Instinctively I’m with you on this one, but my worry is over how you get Joe and Hans in the same room together? I imagine, assuming they are both online already, that the webspheres they inhabit barely overlap at all, just because of the language issue, and I’m a believer that eParticipation usually works best when it starts from where the people already are. So tools to promote a European public sphere need to find clever ways of a/ signposting people from their ‘home’ discussion spaces to trans-national spaces (which would be the best, but most difficult solution) or b/ achieving a sort of secondary integration, for example through services that can summarise and find common points among the topics being discussed among Europe’s different language communities. Your blog gavesome good examples of the second type (Global Voices and Café Babel); do you know of any examples of the first?

By Zebralog on Jan 26, 2009

Signposting people from their home discussion spaces to trans-national spaces is not difficult, if you change the discourse-design. Instead of discussing in a completely open community, one can opt for a (large) random-panel. If you do that, signposting becomes a project-task at the beginning of an international consultation, which might be expensive but not impossible.

The positive side-effects of this include a higher credibility of the voting- and discussion-results, because you have better demographic information about the participants.

By Hans Hagedorn